Homemade Pemmican: Canada’s First Energy Bar in FEAST!

Homemade Pemmican! Salmon and Saskatoon Berry Pemmican presented by Chef Shane Chartrand on the shoulder bone of a moose.

Look at that gorgeous dish! It was called the Great North Pike Plate and featured Northern Pike with burnt sage topped with fried pemmican and wild high bush cranberries. I foraged the High Bush Cranberries for the above dish that evening and have never forgotten it. Since that plate 5 years ago now, we have tried to get together for him to demonstrate pemmican making. Eating pemmican was on my bucket list. How can one claim to be Canadian and never tasted pemmican? Well, that is how it is for most of us. So many stories of aboriginal people and food through my life, but never the opportunity to eat, taste or cook any. One of the fundamental tenets of Eat Alberta was just that. It is still a goal of mine and I believe fundamental to my Canadian cultural identity. After I ate that delectable pemmican, making it myself was next on that bucket list and today, it is finally happening!

Pemmican has only three ingredients: dried meat or fish, dried berries (or mushrooms) and fat. Those three items together are packed with everything one needs to survive in the wilderness for long periods of time. But, some varieties are not very palatable to the modern tongue.

Most pemmicans served in restaurants or at catered events are highly seasoned and have additional flavourings or dried foods added for appeal, and this can be done without messing with the foundation of the dish. A moose or bison pemmican is more appealing to me, personally. I adore all fish, but dried fish tends to be – well – fishy. Not the candied dried fish. Not cured salmon. But bone dried fish. And, in a pemmican, can take over the flavour profile. Berries are there for nutrient value, but lost in the tasting when a strong fish is the protein. The pike offered a gorgeous balance with the high bush cranberry. Each held their own in the mix and created a bright and lively pemmican. Of course, there were seasonings, and it was also fried! There is much to learn about one of Canada’s first foods and Chef Shane Chartrand is a gifted teacher.

Homemade Pemmican: Introducing Chef Shane Chartrand

This recipe for homemade pemmican is also in my favourite new cookbook this year: FEAST!!!! (I have a recipe in it, too! Such an honor!)

I first met Shane many years ago when he was working at L2 Restaurant at the Fantasyland Hotel in West Edmonton Mall. I called him for a meeting to make a pitch: please come and present to our first ever Eat Alberta conference. I revisited that pitch for the next 4 years and this year, he will be there, but I retired from that baby 2 years ago, though am tickled pink others will learn from him there. If you haven’t registered for it yet, do so here.

The next time I worked with him was when I asked him to create a course for our Slow Food in Canada Conference Gala at the Enjoy Centre when it had just opened in Edmonton in May of 2012. He made that gorgeous Pike Pemmican dish that evening that was so unforgettable. Of course, there have been so many times throughout the years our paths have crossed. I’ve had the pleasure of judging his food at a couple of the Culinary Arts Cook Offs. He works a kilometer from where I live and has invited me to some of his tasting dinners. (And I hope to be invited to more!) I think you can see that I am a fan.

Above, Shane is holding the latest cookbook he is featured in: Feast: Recipes and Stories from a Canadian Road Trip where you will find this pemmican recipe! The exact recipe in the book is below the recipe I have written from our experience together.

Currently, Chef Shane is in the process of finishing authoring his first cookbook: MARROW: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine.

Shane hails from Aboriginal Alberta roots via the Enoch Cree Nation though he grew up with his adoptive family on a farm outside of Red Deer in the Penhold area in the early 1980’s. His early life was an acute mix of longing for his aboriginal identity and living the life of a typical Canadian prairie farm family. However, he hunted, even with a bow and arrow, fished, went on survival trips, and learned to love and revere nature from his adoptive father who wanted to somehow provide him a frame of reference for the people from where he had come. I was honored that Shane shared his story with me. Suffice it to say that his adoptive parents rescued this young lad from a life of foster care at 7 years old and in their home he learned love, respect, religion and so much more. Later, in his early adult life, he learned about his roots, met some of his family and it is clear to me that the gift of his birth parents is the never ending resilience and powerful perseverance within his spirit. Those should be Shane’s two middle names. I think it is clear that I am a fan.

Shane hails from Aboriginal Alberta roots via the Enoch Cree Nation though he grew up with his adoptive family on a farm outside of Red Deer in the Penhold area in the early 1980’s. His early life was an acute mix of longing for his aboriginal identity and living the life of a typical Canadian prairie farm family. However, he hunted, even with a bow and arrow, fished, went on survival trips, and learned to love and revere nature from his adoptive father who wanted to somehow provide him a frame of reference for the people from where he had come. I was honored that Shane shared his story with me. Suffice it to say that his adoptive parents rescued this young lad from a life of foster care at 7 years old and in their home he learned love, respect, religion and so much more. Later, in his early adult life, he learned about his roots, met some of his family and it is clear to me that the gift of his birth parents is the never ending resilience and powerful perseverance within his spirit. Those should be Shane’s two middle names. I think it is clear that I am a fan.

His mom made simple food, but to him, it was always delicious. However, that isn’t why he started to cook. He needed a job to buy nice things and worked in a restaurant, eventually cooking at 17. Oh, he loved it right away! Not because of the food, but because of the toys! The kitchen was stocked with all sorts of fancy-schmancy equipment. He loved and thrived in that environment, felt empowered, and at home.

At 22 Shane completed his culinary training, and almost 20 years later, Shane’s food now focuses on his cultural center. As he studies aboriginal cultures, he consistently deepens his own self-awareness. Working with award winning chefs and training in some of the best restaurants and hotels in Canada throughout his career, has furthered his culinary skills and driven home to him the importance of his aboriginal food foundation.

His most recent achievement was his work with “Cook it Raw-Alberta”. He is featured in the “Cook it Raw-Alberta” documentary, as well as the Alberta Culinary Tourism Alliance Collaboration videos, CHOPPED CANADA and been a Redxtalks Speaker. What does his future hold? It is jam packed, but the most exciting upcoming happening in Shane’s immediate future is his involvement with Terroir! If you haven’t book your ticket, do it now: Our Home and Native Land: Celebrating Canadian Gastronomy.

Homemade Pemmican: A Brief History

Pemmican is one of the most concentrated foods known to man. It will sustain life indefinitely and needs no refrigeration. Pemmican was rationed for emergency use due to the incredible labour involved in making it. Fresh meat was killed whenever possible, and what was not needed, was dried for later. The Pouce Coupe [in the Prairie area] was famous for good quality pemmican [from the Dane-zaa people, at the time referred to by the Europeans as the Beaver Tribe], but the Peace River country “exported” it for centuries before the white man arrived.

According to Dorothy, “[Pouce Coupe was raided in the] Peace River [area for the] Pemmican by the Cree and after the fur-trade began, pemmican was [as highly sought after as furs].”

Preparation for Winter included the drying of berries and meat in the summer months for many Canadian aboriginal nations. Dorthea Calverley, 1903-1989, a Northern Dawson City and Peace River Area historian, writes: “The voyageurs west of Grand Portage carried pemmican and supplemented it with wild rice when possible. A man doing hard labour required eight to ten pounds of fresh meat – which he had no time to hunt, dress and cook. Two pounds of pemmican nourished him [in the same manner]. At the night camp he could hack off a chuck and boil it. For breakfast and the noon break he munched it dry. “ She continues, “To the chant of traditional songs, the women beat strips of dry-meat [on] a hollow log, up-ended, and bound with a thong of rawhide to prevent splitting served as a container with stone pounding implements until it was almost like powder. [This] mass was mixed with melted fat in a bark trough, then packed very tightly into skin bags, and sewed up so that no air could enter, folding the skin over until no air remained in the bag.”

Saskatoons and chokecherries pounded up, pits and all added to the flavour, if not the digestibility. Some women, as in any society were very clean and careful when preparing food, and some were not. A well-known good pemmican-maker commanded a higher price as a bride The pouch, or stomach of the animal, was used as a container which seems to bother some, but keep in mind that sausage is made inside of animal intestines.

Homemade Pemmican: Project 2017, Valerie in the Kitchen with YOU!

Some women like to shop or go to the spa. I love to cook in my kitchen with a friend – or someone learned who has a recipe to share, and a story to tell. Essentially, I want to glean heritage and traditional recipes – the best of the best – from our oldies and goldies that have so much experience in their heads. I want to cook with our babas and nonnas and grandmas and grandpas and learn to make what they are known for, or famous for, and share it with my readers. This is not exclusive to our elders, but definitely with them in mind. Of course, many, many younger folk, like me, for example, have much to share, as well. I have also had a deeply rooted desire to learn so much more about aboriginal food.

#ACFValerieCookingwithYOU!

Shane and I are making homemade pemmican! One of the first Canadian recipes, and I only hope and dream I will have the opportunity to cook in my kitchen with aboriginal home cooks, as well.

If you would like to participate, please let me know!

- Project 2017: Cooking in the Kitchen With… Completed Project Posts here.

- Project 2017: Cooking in the Kitchen With… Cooking Schedule is here.

- Project 2017: Cooking in the Kitchen With… PARTICIPATE!

Homemade Pemmican: Mis en Place

Shane prepared the salmon for this recipe. I prepared the berries, but he did some berries, as well. Three simple ingredients: dried meat or fish, dried berries or other dried forest flavours (mushrooms etc) and fat. Equal parts of each, usually. Sometimes a little more of one than another, but always at least 1/3 fat.

Homemade Pemmican: Drying the Meat

Shane used 3/4 of a side of Chinook Salmon or about a 2 pound filet that he sliced very thinly and submerged in a dip. He let it sit for a day after dipped, then patted it dry, sliced it very thinly and dehydrated it for 18 hours. This is dip in not offered in the Feast Cookbook Recipe. Dip Ingredients:

- 1 cup honey

- 1 cup maple syrup

- 2 tablespoons each minced garlic

- 2 tablespoons each minced shallots

- 1 teaspoon fresh dill

The salmon almost shreds itself as it gets turned during the drying process.

We now know the salmon needed drying for another 6-12 hours, but look at how lovely it appears, above. And, it definitely made a lovely homemade pemmican, but every bit of moisture must be dried from the protein to enable the pemmican a “forever” shelflife.

Homemade Pemmican: Drying the Berries

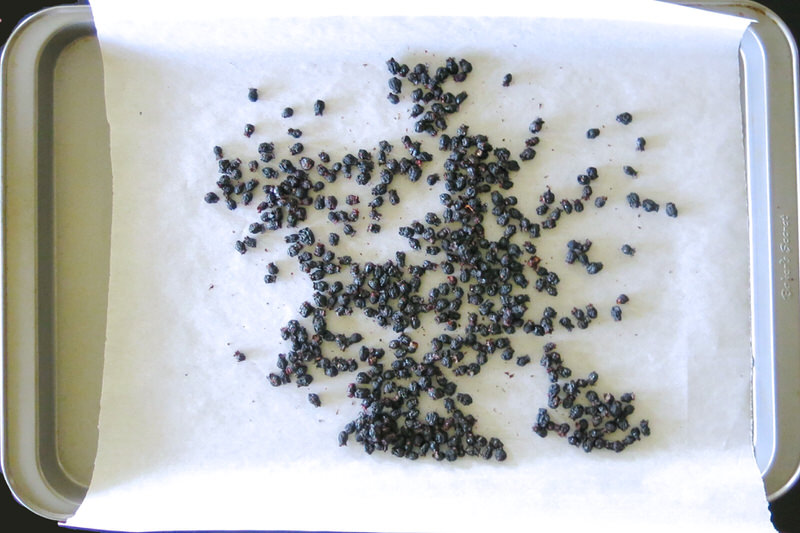

Frozen berries work as well as fresh. What really blew me away was how few berries there are after the drying process: above, left – over 2 cups of plump Saskatoons; above, right – less than 1/2 cup of them left. Such a small amount!

Into the oven at 170F on convection dehydration for 20 hours.

Above left, lots of staining on the paper, and such tiny berries, so I moved them to clean paper, above right.

The key with both elements in pemmican: bone dry. It is clearly evident that these blueberries were “bone dry”. Look at the gorgeous dust I made by grinding them in my Thermomix machine. It only took seconds. I didn’t waste a sliver. I used a little brush to save every morsel in a bowl. This powder packs a powerful Saskatoon berry flavour punch. Oh. My!

Recall “Lick-a-maid” as a child? Multiply that by 10 for the flavour burst. Pure berry goodness. I was thinking ice cream flavoring, game meat rubs. The ideas of how to use this precious commodity are endless.

As I prepared, dried and ground my Saskatoon berries at home, Chef Shane dried and brought his for the pemmican.

Homemade Pemmican: Making the Pemmican

But, I am a firm believer in not using the toys until you can do it by hand. Grinding the berries and pounding the dried meat with the mortar and pestle with Shane was such a cathartic experience. He said he feels he is far more in touch with his ancestors when he does it their way, and I totally get that. I certainly don’t feel Grandma Maude’s spirit with me when I am whirring my Thermomix!

The colour is gorgeous and the aroma was intoxicating. I really didn’t have any expectations for this day, so every part of it was a gift.

We spelled one another on and off the grinding as we chatted… of course, he did the lion’s share, but I did enough to understand it, feel it and know how.

At this point, I thought we were done. Berries are pulverized, no?

No. Not close to enough. Keep going until they are as fine as the powder that came out of my Thermomix machine. Of course, if you want a textured end product, no need to work for the powder; however, the finest powder creates the most desirable end result.

All righty, then!

And, about 20-30 minutes in, we are done. The berries do take longer as they have seeds that really need to be finely pounded.

About the same amount of salmon went in to the mortar. Time to pound it into dust.

Shane had a lot more than we needed. I was worried the intensity of the salmon would overpower the gorgeous aroma of the Saskatoon berry – and, it pretty much did. Of course, it wasn’t so much about flavour “back in the day”, as it was about nutritive value, though it is clear through the research that some women were well known for the texture and flavour of their homemade pemmican as it was far superior to most. These woman, I imagine, attended to flavour balance and textural qualities.

As Shane had said, the protein pounds out much faster. Above, the salmon is done. You can see it is a little “wet” which later was somewhat problematic. Had we been paying more attention, we could have and should have stopped at this point and dried it longer, to eliminate every bit of moisture. That is a must for making pemmican that will last 10 years or a few life times, as it is noted for.

Pulverized Saskatoon berries are in on top of the salmon, above, and now to combine well, below.

I have magnified the image, above, but the particles should likely be finer for a more refined and pleasing texture. This is a fine enough texture for pemmican, but all relates to the desired outcome: smooth and pasty; gritty and toothsome? What is the desire?

Time for seasoning. At this point, all sorts of dried herbs and seasonings can be added to the mix. Even a mixture of dried fruits up front with dried mushrooms or mushrooms instead of fruit. Keep in mind, there would need to be berries in any pemmican for long term survival.

Shane is mixing in the seasonings.

Now, the fat is to be added.

Typically it would be bison fat, but any tasty fat will do. Shane suggested bacon fat for flavour, so that is what I prepared. Be sure to get every bit of water from the fat. I let mine sit and simmer until all water had evaporated out of the fat before solidifying it.

The formula we used for this hoemade pemmican was about 1/2 pound of the dried Chinook Salmon to 2 cups of dried Saskatoons. When the fat is added, and the berries and meat are properly pulverized and pounded, the mixture appears thick and porridge or pudding-like.

It can be spread on a sheet to solidify, or made into a log and sliced.

Homemade Pemmican: Storing the Pemmican

Kept in a cool place, homemade pemmican will keep for years.

Homemade Pemmican: Serving the Pemmican

After our pemmican making session, Vanja and I traveled over to Sage where Shane is the executive chef, to get a photograph of him with the finished product. He prepared a shoulder bone for plating and singed some rosemary to tie around the end of it. That moment was a ceremony unto itself. The strong aroma elicited emotion and was reminiscent of the sacred ritual of smudging of sage or sweetgrass which is symbolic of much, but to me, at this moment, it was a release of all negativity and the embracing of the power of this past through our shared pemmican making experience.

Shane rested slices on a haskap berry coulis with some thin shards of onion and micro-greens, then garnished all with translucent dried horseradish chips.

And thus, it is.

Thank you so much, Shane, for opening this window into your world and for this gift of time, and teaching me how to make this incredible simple, yet elusive homemade pemmican recipe. Here’s to more time together in our future!

Homemade Pemmican

Canada's First Energy Bar! In the Kitchen with Chef Shane Chartrand of Marrow, Progressive Indigenous Cuisine with step-by-step images. Recipe also in Feast Cookbook!

Ingredients

- 300 grams fresh Chinook Salmon (I suggest pike or moose) or or 100-125 grams dried fish or red meat

- 300 grams fresh Saskatoon berries (or high bush cranberry or haskaps) or 60-75 grams dried berries

- 100-150 grams rendered fat or bacon grease , room temperature, as needed

- ⅛ teaspoon salt , or more, to taste

Possible Additions:

- freshly ground black pepper , to taste

- dried mushroom powder , to taste

- dried herbs , to taste

Instructions

Instructions for Drying the Meat:

- Thinly slice meat; easiest to do when partially frozen or with a razor sharp knife

- Place slices on parchment covered pan, not touching; dry for 20-24 hours at 170F

- Check and turn pan regularly; turn slices over, as needed

Instructions for Drying the Berries:

- Place on lined parchment covered pan; dry for 18-20 hours at 170F

- Check and turn pan regularly; shake berries and move around, as needed

Instructions for Rendering the Fat:

- Instructions here (the recipe is for rendering pork fat for pie pastry, but use beef suet and the same process which will be much faster as protein is already removed from suet

- If using bacon fat ,as is is so flavourful and highly desirable,, ensure it is slowly simmered at low heat so all water has evaporated from it (it should get very hard, like a lard, in the fridge)

Grinding or Pounding by Hand:

- Using a mortar and pestle, grind-pound berried to powder; more grinding than pounding for the berries (there are seeds and it will be more labour intensive than pulverizing the meat)

- Set aside (about 30 minutes of focused work)

- Place dried protein in mortar and pound-grind with pestle; more pounding than grinding for the meat

- Add powdered berries into powdered protein; combine well

Using a Thermomix or Food Processor to Grind Dried Ingredients:

- Add both berries and protein into your machine; puree until powdered

Adding the Fat:

- Stir the room temperature fat into the dried powdered pemmican ingredients a third at a time; test for consistency, but be sure to use the full minimum amount

Adjusting Seasonings and Adding Flavour:

- Add salt, as needed (it will make a lively difference, but little by little)

- Add optional ingredients according to palate: pepper, dried mushrooms, dried herbs, etc

- Taste

Storing the Pemmican:

- Slather flat on parchment; refrigerate and slice into portions to store in a cool space OR

- Dollop onto plastic wrap; form a log and chill for cut off portions for service, as desired

Trouble Shooting:

- If your pemmican does not solidify, you need more fat ; add more fat OR

- If you used bacon fat, you did not expel all of the water and you will need to start again

Serving Pemmican:

- Slice very thinly and serve with popped wheat berries, thinly sliced ribbons of bannock and a berry coulis (same berry that is in it) garnished with fresh herbs (echoing the herbs, if any, in it) OR

- Slice thinly on a cracker OR

- Slice thinly; fry and serve with any garnish or on a cracker

Hiking with Pemmican:

- Pack it well wrapped and store in the coolest place possible: experiment with how to eat it - jerky-like, boiled and mashed, fried...

Notes

Pemmican with Saskatoons or Blueberries from FEAST

Serves 4 to 6

Pemmican is a traditional First Nations food made of ground dried meat and berries mixed with fat; it’s a high-density staple designed to help people survive long winters. Traditionally, its preparation involved hunting or fishing followed by sun-drying the meat, grinding it to a powder with stones, mixing it with fat in equal parts, and storing it in raw animal hides. This is a modern pemmican recipe contributed by Shane Chartrand, a Plains Cree Edmonton chef, and is a slightly sweet and very sustaining snack. Because it keeps so well, it’s a perfect protein source for multi-day hikes.

1 pound (454 g) bison, salmon, Arctic char, or pickerel

1 cup (150 g) fresh Saskatoon berries or blueberries

6 to 9 Tbsp (85 to 128 g) rendered fat or bacon grease, room temperature, as needed

⅛ tsp salt (optional)

First, slice the meat as thinly and consistently as possible so the pieces dry evenly. If using bison or another lean game meat, remove any large pieces of fat, as these will not dry out consistently with the meat. If using any kind of skin-on fish, remove the skin and thinly slice the fish.

Preheat your oven (or a dehydrator, if you have one) to 145°F (63°C). If your oven doesn’t go that low, preheat to its lowest setting and prop open the door 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 cm) while the meat dries. An oven thermometer is really useful here.

Distribute the sliced meat evenly over metal racks (cooling racks work well) and place the berries on a parchment-lined baking pan. Place on opposite sides of the preheated oven and let dry for 20 to 24 hours. Alternatively, if using a dehydrator, lay the sliced meat and berries on opposite sides of the tray(s) and let dry for 24 hours.

Once dried, transfer the meat and berries to a food processor and blend until very fine. There will likely be pieces that still need to be crushed with a mortar and pestle, or you can choose to leave those pieces whole and have pemmican with a slightly coarser texture.

Starting with 6 Tbsp (85 g), mix the room-temperature fat or bacon grease with the ground meat and berry mixture until incorporated. Add the fat 1 Tbsp (14 g) at a time until your desired texture is reached, keeping in mind the mixture will firm up once refrigerated. Transfer the pemmican (you’ll have about 1 cup at this point) to a piece of plastic food wrap. Shape into a 1-inch (2.5 cm) diameter log, roll tightly, and twist the ends to keep it together. Store in the refrigerator; when needed, cut off a piece and rewrap. Pemmican will keep for a very long time, especially when refrigerated, but it’s best consumed within 2 to 3 months.

Thank you Valeria for sharing this incredible experience with your readers. Respectful and educational. Sharing a piece of our Canadian history very few are privy to, makes me want more. Thank you to Shane M Chartrand for sharing your passion of food and bringing your heritage front and center.

Thank you so very much, Jodi, for making the time to add your facebook comment to this post. This is such an important part of the blogging and archiving process as it provides readers with an account and an opportunity to participate in a conversation with others over a much longer period of time.

Hugs.

Valerie

Sounds fascinating. I hope I can try Pemmican when I travel to Canada.

Gorgeous photos and great storytelling — makes me want to make pemmican immediately! Keeping the recipe for a rainy day.

🙂

Great recipe and beautifully presented. Thanks for sharing!

This looks, AMAZING! I have been wanting to make a salmon-based pemmican. I’d long to get this book as well, thank you for sharing such a lovely, wholesome, indigenous creation.

Lovely to hear!

Let me know how it goes!

🙂

Valerie